An Unexpected Revolution

In late 2020, I was introduced to a book that unexpectedly revolutionised the way I ran. Titled ‘The Lost Art of Running: A Journey to Rediscover the Forgotten Essence of Human Movement’, the book was authored by Shane Benzie, a running technique coach and movement specialist. Benzie had travelled extensively across the world and worked with diverse groups of athletes and indigenous peoples in some of the most extreme environments in the world.

Fascia: The Thin, Fibrous, Stretchy Tissue

Like me, Benzie’s revelation occurred unexpectedly; it was his attendance at the ‘Myofascial Anatomy and Dynamics Workshop’ that triggered the change. “Many people have become increasingly frustrated by the anatomy of individual parts.

We have this very sophisticated system of labelling everything, yet when we see an animal or a human moving, we see a complete integrated body,” the speaker, James Earls, proclaimed, “The inconvenient truth is that our conclusions in anatomy just don’t stack up.”

Earls then told his audience to envision portioning a large slab of raw meat and to pay special attention to the tissue that surrounded each piece - the fascia. It was dull and grey, easily missed but vitally important. “Fascia is the fabric that holds us together,” he continued, “Appearances can be deceptive. Fascia is - quite literally - one of the most dynamic things in the human body”. Fascial bags hold organs and muscles together. Every individual muscle fibre and each bundle of fibres were held in place by a series of fascial bags, coming together at the muscle ends to form thick, strong tendons. “When you stretch them, these tissues capture and can momentarily store the resultant energy before returning it into our system to help us move,” asserted Earls.

Think of how an elastic band works. As you stretch one end of the band, energy is stored up till the point when the band is released and it springs back into its initial state. The fascia works similarly as a web of stretchy fibrous tissue that envelops your entire body. In other words, elasticity is literally embedded within you.

Tensegrity: Short for ‘Tensional Integrity’

Contrary to popular belief, the skeleton is not a stabilising structure from which everything else hangs. Instead, as Benzie noted, “our bones float in the soft tissue - in a sea of tension - and that the soft tissue adjusts the stiffness of the system in response to the forces acting on the body”. Unlike the screws and wires that hold the dummy skeleton in your local science lab, it is the myofascial system that holds everything together in reality. But what does this imply for running?

“Each bone has its own little trampoline that it sits in and it will bounce within that trampoline following every foot strike,” explained Earls, “As ground reaction forces push up, gravity pushes it down and momentum encourages it mostly forwards. Like a trampoline, each deceleration experienced by the bone will stretch the surrounding springs or, in our case, the elastic tissues, and this helps us increase efficiency of movement. It is all a suspension system helping to dissipate landing forces through the body so the shock of impact is not taken only by the foot or isolated to the lower limbs. The forces are also spread into the elastic myofascial tissues to load elastic energy, which can then assist with the recovery movement”.

Put simply, the tensegrity system harnesses the fascia’s natural stretchiness and bounciness to propel movement. It works just like how you could pull an elastic band back and forth to create fluid motion. If you stretched it, the band recoiled back to its initial state. If you compressed it, it functions like a spring. If you tried to pull it apart, its resistance is inspiring. Let us now consider how to harness our potential to be elastic, synergistic, fluid and connected in our movement.

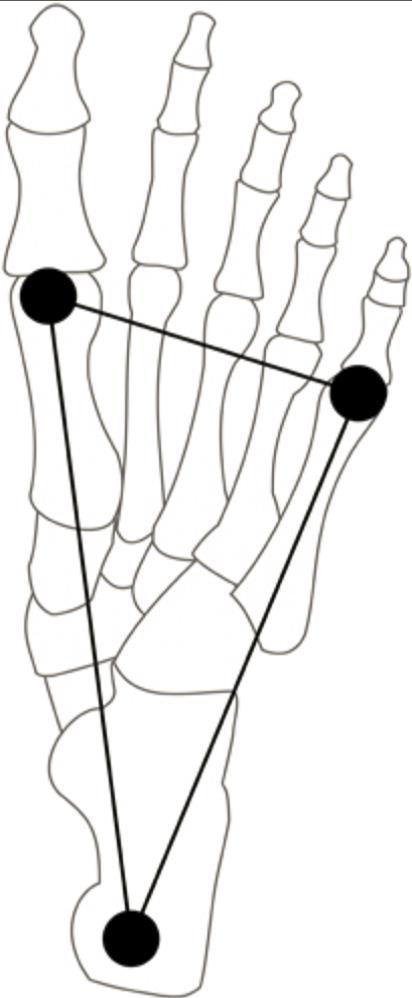

Foot Placement: Tripod Landing

What is the best way to dissipate impact? Imagine dropping a bowl to the floor. What happens if the whole lip of the bowl lands on the ground at the same time? The bowl makes a hollow pop as the impact is dissipated equally around the edges. Unless there are preexisting fault lines, the bowl is unlikely to break. But if the bowl lands on an edge, it is very likely that it would break at the area of impact.

Applying this principle to our foot, Benzie advocated for a tripod landing. This takes advantage of our natural ‘dome’ (arches) by landing with a full foot. Benzie was particularly critical of heel striking, noting that “All of the force from landing will go up through that straight leg, sending shocks through your ankle and knees and making next to no use of the natural elasticity in your body … With one foot always on the ground and with little to no height in their stride, what they are in fact doing is walking”.

Benzie believes that one of the reasons why we regress into this style of fast walking is our fear of impact. Running loads our foot with several times our bodyweight, so it’s not surprising that impact is viewed as running’s nemesis. Many believe that impact causes injuries and hence should be minimised as much as possible. Shoe companies capitalise on this fear by selling maximalist shoes and cushioning systems that promise to reduce injury rates. Runners on their part consciously force themselves to pitter-patter around as if running on thin ice because they are afraid of the ground.

Are such fears justified? While Benzie did not directly address these claims, he is convinced that impact is inevitable and runners should instead make good use out of it. “Every time we make contact with the ground, it’s an opportunity to create elastic energy,” he claimed, “we do this by loading our body and propelling ourselves forwards using our elastic system”. Visualise your foot as a spring: each time you land, the impact is absorbed by the ligaments, tendons and muscles as they tense up and returned with elastic force when we propel ourselves forward. The lesser the impact, the lesser the energy transferred and we find ourselves sinking into the ground.

Does this mean that runners should land with excessive force to maximise said elasticity? Absolutely not, that’s a recipe for disaster. There aren’t many springs that can withstand a hydraulic press. Even if they do, they’ll be severely bent out of shape and lose all elastic properties. So how much force is ‘enough’? Here is where the importance of proprioception comes in.

Shoes: Trade-off between Proprioception and Protection

Shoes change our perception of our movement by dulling our sense of the ground. To be clear, Benzie does not advocate for a particular type of shoe. What matters for him is how much the shoe affects our natural elasticity by influencing proprioception. In this regard, minimalist shoes often do ‘too much too soon’ by placing tremendous strain on our lower leg muscles and tendons, particularly on the calf and Achilles. Injury thus becomes a significant possibility especially if the runner in question is a long-time heel striker transitioning to a forefoot strike.

On the flip side, Benzie discovered that runners consistently recorded significantly more impact forces when running in maximalist shoes. He surmised that this was due to two possible reasons. First, having a thick wedge of cushioning meant that the runners’ perceived themselves to be

protected and can hit the ground harder. They therefore land harder and end up putting more force through their legs. Second, runners hit the ground harder as they have no idea what’s going on under their feet. Without sufficient sensory feedback, our ability to move well is hindered.

Runners thus tend to land more forcefully to make up for the lack of sufficient ‘ground feel’.

With these considerations in mind, Benzie concluded that what we really should do is to “ask ourselves how much rubber we really need between ourselves and the ground. It’s a trade-off between proprioception and protection. We want to protect our feet from the elements but also allow those ingenious things to do their work.” For him, shoes should be designed to allow runners to move through their environments efficiently (grip for rocks and mud etc.). There isn’t much point in a shoe that claims to add a spring to our step if our interaction with the ground is incorrect to begin with. In reference to the current proliferation of expensive shoes, Benzie stated that “We cannot buy our way out of trouble. There isn’t a pair of trainers in the world that I think enhances performance. They all to a degree inhibit it - it’s just about how much. What we should be investing in is good, efficient movement. And, if we get it right, this can truly enhance our performance. What’s more, it’s completely free”.

Cadence: Between 175 and 185 Steps per Minute

When the aforementioned James Earls was posed the question of what the best running cadence should be, he replied that “The way in which we land is designed to maximise the elastic energy by optimising the energy captured and ensuring it is efficiently returned to our system by using a 180 cadence. If the energy is held for too long in the fascia it begins to dissipate and is lost to us, a process called hysteresis. Turnover of the stride is therefore equally important if we wish to be ‘elastic runners’”. In other words, our optimum cadence would be somewhere between 175 and 185 steps per minute as this is our body’s natural frequency associated with the creation, storage and release of elastic energy.

However, by focusing solely on cadence, the runner in question would merely be shuffling around with quick feet, a shorter stride and most importantly, getting very little from vertical oscillation. As a result, the runner would therefore be “completely sucked to the ground, far less dynamic and most likely struggling with their breathing”. But why the emphasis on vertical oscillation? Doesn’t an upwards bounce signify wasted energy, as critics tend to say?

Stride Length: Create a Bounce that takes us Upwards and Forwards

Cadence and stride length are inseparable. If we overstride, it would be difficulty to increase our cadence without dramatically shortening our stride length. As noted previously, even if we managed to increase

our cadence, we would likely regress into a pitter-patter that has us sucked into the ground.

(Head tilted down, tight shoulders, bending forwards at the waist)

Contrast this with elite Kenyan runners. Chances are that they run upright, lifting their knee in a cycling motion and landing with a tripod platform, knees bent slightly with the other leg already on the way back. A powerful form that looks both beautiful and effortless. Throughout the entire gait cycle, their whole body remains tall and upright. Their strides are fluid and they spend very little time on the ground. Notably, they are not visibly accentuating their stride length. Their leg do not stretch out far forwards. And yet Kenyan runners do record some impressive stride lengths. How is this possible?

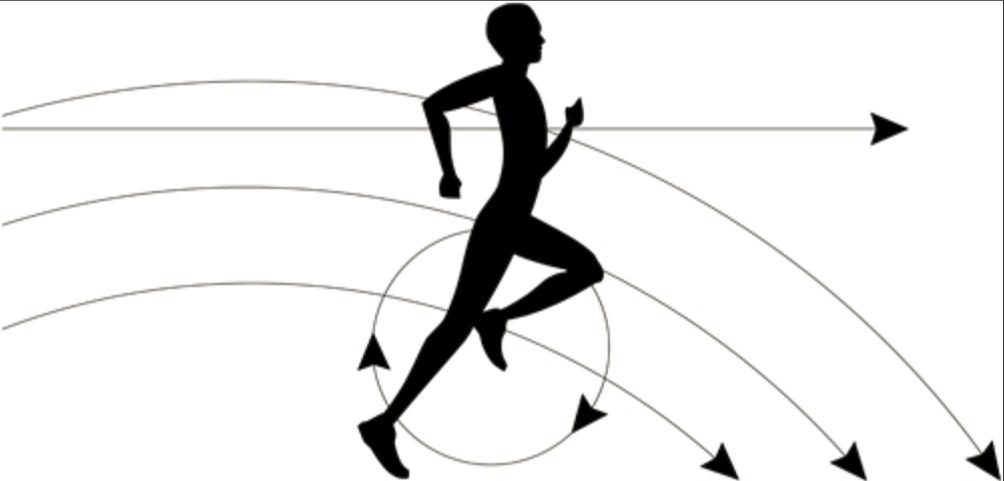

The secret is to create a bounce that takes us upwards and forwards. As Benzie said, “If we are moving forwards through the air and cycling our legs underneath us as we go, we will land further forwards than we would have but with our foot making contact underneath our body. Height essentially gives us room to work”. Consider his illustration:

By gaining some height to cycle your legs, you would be able to land further through your running cycle. This also means spending less time on the ground and not shortening your stride.

Posture: Tall and Upright

Utilising our fascial system will allow us to take full advantage of our body’s natural elasticity, thereby reducing the workload on our muscles. Muscles tire and need fuel, so it helps to alleviate some stress from them. If you run hunched over and slouching, the elastic bands running through your body will have very little recoil to return significant elastic energy. But if you run tall and upright, you will pull those elastic bands tight and develop a natural recoil that propels your muscles. And the best part? The fascial systems does not require fuel like muscles do and they don’t tire. If you want to move efficiently and effectively, then make use of this natural elasticity.

our elastic system

Alas, our dynamic posture is highly dependent on our everyday posture. How we stand, walk or sit will affect how we run. We are what we repeatedly do; good and bad habits will deeper ingrain themselves the more frequently we perform them. As such, it is imperative that we don’t sabotage ourselves by repeating bad habits. Whenever you feel the urge to slouch, imagine giant elastic bands running up from your toes to the top of your skull. Consciously remind yourself to stand upright, not be held upright. When running, run tall with your chest out; create a bow-like form, with eyes gazing upon the horizon. Feel the elastic tension in your body and utilise your posture to pull the fascial system tight to take full advantage of the body’s natural elasticity.

Lean: Not from the Waist, but from the Ankles

A forward lean contributes significantly to our propulsion by employing gravity in our favour. The problem is that runners are typically taught to bend forwards at the waist in order to lean. What we should be doing instead is to fall forwards from the ankles to ensure that the whole column of your body goes with you in a bow-like form. The more we lean, the more our stride opens up to accommodate the lean. As such, lean more to speed up as our stride increases, lean less and our stride shortens and slows us down.

Take Ownership of Your Movement

The human body is designed to move, and movement is what will make us better athletes. The problem with today’s sedentary lifestyle is that many of us have simply forgotten how to move beautifully and efficiently. Practising running as a learned skill rather than treating it as a series of mechanical movements can be both liberating and exciting. Don’t think of yourself as a stiff, creaky body comprised of countless parts. Instead, think of yourself as being elastic, fluid, connected and synergistic.

When changing or adopting new movement patterns, the initial shift will feel tiresome and draining. This is natural and expected; your body is expanding more effort to (re)learn movement patterns. The brain naturally craves efficiency, even if that means being efficiently inefficient. I urge you to persevere through the initial weeks of transitioning as the rewards of moving beautifully and efficiently are tremendous. The new movements will feel awkward and difficult, but in time your brain will realise that it is more efficient and will eventually embrace it.

The best way to strengthen the body for running is to simulate dynamic running movement. This is near impossible with most running drills and specific strength exercises as they are not designed with a synergistic body in mind. Alas, the best way to improve your running is to run. Do not do intervals solely for the aerobic benefits, but do so also because intervals are an opportunity to improve your running form. Focus less on mileage and more on beautiful relaxed movement. Five kilometres of running with a good form will confer more benefits than 10 kilometres of slogging through with a bad form.

Take ownership of your movement. Run beautifully.

~

Note to Readers:

I give full credit to Shane Benzie for all the ideas, concepts and illustrations that are present in this article. I have incorporated his advice on harnessing elasticity in my running form and have experienced the benefits firsthand. It is with this confidence in his teachings that I now share my key takeaways with the wider running community in Singapore. As Benzie said: “It’s never too late! Start taking ownership of your movement. Trust me: it’s the best investment you will ever make”.

Comment (0)